testing, one two

testing your patience

Welcome back to the last blog at the end of software engineering. Pull up a stool. I’m here to give you my take on testing.

Wait, wait, don’t go. I promise, it’s worth reading. I typed these words by hand.

Why would testing be an important topic now, of all times, especially considering how many of us are likely using tools to generate our test suites and those same tools to generate fixes to said test suites?

Well, strawperson, I would argue that tests are more important now than they have been for a long time.

You have two feedback loops available to you. You can get feedback from your users: they can tell you your program is broken explicitly, if you’re lucky. If you’re unlucky, they’ll tell you this implicitly by not using your product.

Tests are your other feedback loop. They’re the cheap one. Good tests will tell you something about your system as it changes. They give you confidence that a change to one part of your system won’t set the other parts on fire. Tests keep your generative coding tools on track.

Let’s back up for a second to talk about what a test suite actually is: I find that most developers I talk to think of a test suite as an ancillary component of their program. Tests are a property of the important code in the code base: you might talk about “a module and its tests”. The codebase is mostly about their shipped program, application, or service. Tests say whether that program is “Of Kwalitee”. I mean, “Of Quality”.

To which I say: look again! Each test case you build is a program unto itself!

This is less apparent in VM languages like Python, Ruby, JS, or Java. Compiled languages make this explicit: Rust and C++ tests are compiled into their own binaries and run via a harness. So you’re not shipping one program, you’re shipping (potentially) hundreds of programs. And the codebase really contains a system whose internal interfaces can be used to assemble these programs, one of which actually happens to be your production application.

The goal of the other 100 programs is to tell you what happens as a result of your changes to another part of that system before a user tells you. If this is designed well, failures in your test suite help you track down which invariant your changes violated. When designed poorly, test suites tell you only that something in your system changed.

You usually see this when the tests over-specify behavior based on internal interfaces. This falls out of treating tests as an afterthought: new components each get a suite of tests. As new components are added suites of tests for new components overlap the old: in order to pass both sets of tests the components must behave exactly as originally implemented, including their internal structure. The overlap violates modularity, in other words.

Instead…

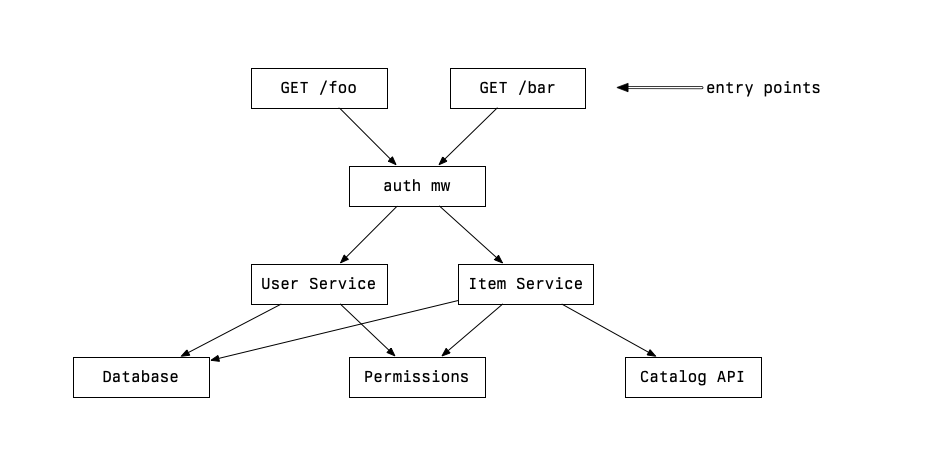

Think of your implemented system as a directed graph. A step abstracted from a control flow graph, but more concrete than a UML diagram. The nodes represent some business logic happening, and the edges between those nodes are interfaces for calling and returning values. Something like this:

When you test, you pick some entry and exit interfaces to test, and in doing so you end up executing a sub-graph of the system under test. I am going to refer to this sub-graph as the “gamut” of your test, in its sense of “complete range or scope of a thing.”

Writing an effective test suite means thinking about how the gamut of each test relates to those around it.

Write tests. Not too many. Mostly integration.

You might be accustomed to thinking of tests that have a narrow gamut as “unit tests”, and those with a wider gamut as “integration tests.” To this, I’d say: “yes, and!”

Yes, and these specific terms imply a frame of reference. From the frame of reference of your system, you might be running a unit test of a single free function. But if your system is a Python application, from the perspective of the Python interpreter, you’re running a pretty broad integration test of the language runtime. (I don’t love these terms for this reason: the definition of “unit” depends on whose ruler you’re using.)

That being said.

When designing tests, you’re looking to identify interfaces which are unlikely to change frequently and which cover meaningful swaths of application behavior.

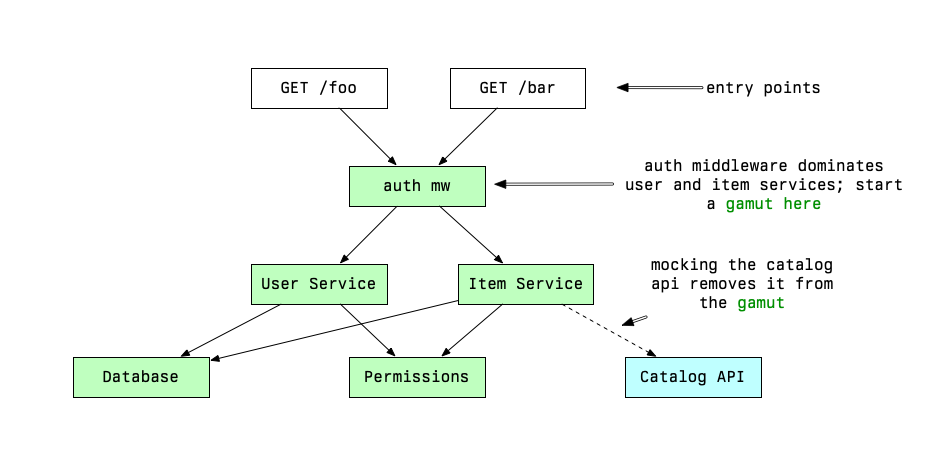

Dominance in a graph describes the property of “flow” through a node with respect to an entry point1. If all paths from an entry point node must pass through a given node to reach downstream nodes, that node is said to dominate the downstream nodes.

Dominance originated in a paper on the analysis of flow diagrams. It has been a useful concept in compiler research, in particular static single assignment form.

This is the property you are looking to build tests around. This lets you “cover” many internal interfaces while starting all of your tests at the same point. If you’re building a REST API, you’ll usually see this along the HTTP endpoints you define. If you’re building a React app, you’ll find this along pages and in commonly used components.

These dominators help design your test suite: you can take that and walk from

the smallest sub-graph with the most overlap – like authentication in an API –

out to tests that depend on larger swaths of the system working in concert. My

druthers is to number these, like I’m building a proof of the system: if

01-authentication fails, I know I can safely ignore errors from

08-frobnicate until I’ve resolved them.

I’ve talked about picking which interface to start a test’s gamut. Mocks are a complementary, inverse tool for determining a test’s gamut. They artificially limit the test’s gamut. Mocks require knowledge of the internal interfaces.

This can be fine: mocking implies knowledge external to the program about whether the interface is likely to change: you might know that the interface to an external API you’re using will not change. You might know that contract-based tests are in place. You might know where the person providing that interface sits in the office and you might be within throwing distance of them.

But you’ve got to be careful: the goal of picking complementary dominators and testing them in order is to build a proof of the system that avoids leaning on internal interfaces. The act of using mocks pins internal interfaces.

Be deliberate about the interfaces you pick to use in your test suite. It’s worth sweating the details. You will produce a crisp definition of what it means for the system under test to fail. These failures will have better context: why is the failure important, what does it affect, and where did it happen first, approximately? And more context will help your agent to avoid spinning itself in circles trying to fix over-specified tests: you can trust that it won’t resolve the issue by rewriting the test.

And that’s the end of my spiel. Aren’t you glad you sat down to read this while your agent finished writing your tests? Go tell them to pull up a stool and read this article, too.